The Unsolved Murders of Milwaukee's South Side

In the 1970s, at least six young women were murdered under similar circumstances in and around Milwaukee's South Side. Authorities had a prime suspect, but couldn't prove he was responsible.

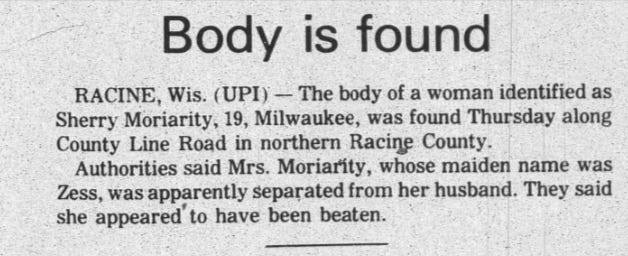

On Thursday, May 29, 1975, a young farmer named Gerald Drought tended a field outside Raymond, Wisconsin, a small town in northern Racine County about 20 miles south of Milwaukee. As he made his rounds on a tractor, Drought noticed something peculiar in a ditch off County Line Road: a human foot.

Drought called on a neighbor, who reported the finding to police in nearby Franklin. When they arrived on the scene east of Highway 45, police found the lifeless body of a young woman lying face down in the weeds. She had no visible wounds, though her head was bruised, and it appeared as if she had been beaten.

The next day, the woman was identified by her parents as 19-year-old Sherry Lynn Moriarity, a resident of a small town outside Milwaukee. Sherry was married but reportedly separated from her husband. Investigators believed her body had been in the field for a day or two before it was discovered.

There was little to suggest what happened to the battered teen. Autopsy results weren’t immediately conclusive, though blood found underneath the woman’s nails suggested she had fought back against her assailant.

Several of Sherry’s belongings were missing, including a gold earring, the butterfly pendant necklace she wore regularly, and personal items from her purse, such as glasses and a hairbrush. Later court documents revealed that one of Sherry’s wrists “bore a mark three-eighths of an inch in width,” leading investigators to believe someone had handcuffed or bound her before she died.

As the investigation unfolded, police learned that Sherry had been last seen on May 24, five days earlier, when she had walked home following an argument with an unknown man.

Sherry’s murder was disturbing, but it wasn’t a lone incident. From December 1973 to May 1975, when Sherry was found, six young women from around Milwaukee had been found murdered, all under mysterious and similar circumstances.

On December 13, 1973, 27-year-old Stena Weber left home to pick up a pay stub from the Milwaukee restaurant where she worked, but she never arrived. The following day, her niece discovered her body in a garage behind Stena’s South Side home.

Two days later, on December 15, the body of 19-year-old Linda Frank was found in a parking garage three miles away from where Stena was killed. Linda had left her boyfriend’s house in the early morning hours of Saturday and was found later in the day by a concerned cousin.

Both women had been strangled, and police admitted the cases that had occurred so close together in time and proximity were “very similar.” There were no obvious suspects, and a lack of progress on both cases “planted a note of fear” in the South Side community, reported one newspaper.

That fear worsened when another woman, 21-year-old Cynthia Marie Franckowiak, was found strangled on January 19, 1974, just one month after Stena and Linda had been murdered. Cynthia’s body lay in a pool of blood in a Milwaukee parking lot just a few blocks from where she lived.

Cynthia had visible bruises and marks on her neck, leading police to believe she had been strangled with a rope or cord. Investigators found cash and a paycheck on her person, suggesting the crime wasn’t a botched robbery. Despite the harsh winter conditions, the driver’s side window of her nearby car was down. The car’s ignition still held her keys.

Months passed before the next victim surfaced: in August 1974, the body of 21-year-old Susan Wicinski was discovered by crab fishermen on the Root River about six miles northwest of Racine. Susan was last seen in an alley near her home on Wednesday and reported missing the same day. Her body had been in the river for less than 24 hours, said Racine Chief Deputy Donald Nelson.

A medical exam revealed that the Milwaukee woman had water in her lungs, but confirmed that she had been strangled to death before being dumped in the current—likely from the Highway 31 bridge just below 4 Mile Road. Susan was missing a pin and a pendant necklace.

Less than two months later, on October 1, the body of 15-year-old Wendy G. Brown was found in a Racine cornfield west of I-94. Wendy, who had been reported missing on August 21, was clothed, though her Mickey Mouse watch and macramé bracelet were missing.

Her body was decomposed to the point that it obscured her cause of death, but the coroner didn’t rule out strangulation. The teen had planned to meet a friend at a drive-in restaurant in Milwaukee’s South Side, but never showed up.

Sherry Moriarty’s murder in May 1975 brought the tragic toll to six young women dead in 18 months. A lack of evidence had stymied investigators—until an unusual event in June 1975 pointed detectives toward a key suspect.

On June 23, 1975, a 20-year-old woman was driving on the North-South Freeway near the Milwaukee-Racine county line when she heard a bullhorn behind her: a police car ordering her to pull over.

When she did, a man claiming—unconvincingly—to be a state police officer handcuffed her at gunpoint and forced her toward his vehicle. Thinking quickly, she asked him to turn off her headlights before they left. When he walked back to her car, she jumped into the driver’s seat of his vehicle and sped away, narrowly escaping her would-be abductor.

The attempted kidnapper was later identified as James Multaler, a Wisconsin man in his early thirties with a curious criminal background. Multaler, born in 1944, had bounced around various small towns in Wisconsin, committing a number of petty crimes and minor traffic violations in his twenties.

In 1968, 24-year-old Multaler had been charged with carrying a concealed weapon in Little Suamico, Wisconsin. He was previously on probation for failing to make a mortgage payment, so the gun charge led to a two-year prison sentence in Green Bay.

Upon Multaler’s release from prison, his crimes escalated. In April 1970, he picked up two female hitchhikers, Mary Mayo and Shirley Wolfinger, in Fond du Lac and drove them southwest to a property in Waupun, where he attempted to rob them at gunpoint. Somehow, the women managed to disarm him during the incident, and as he fled, they recorded his license plate number.

After fleeing the Midwest, Multaler was arrested in Florida and taken back to Wisconsin to face attempted robbery charges. One day, while in the Fond du Lac County jail, Multaler complained of stomach pains and was sent to St. Agnes Hospital, where he escaped from a third-floor window.

A police report claimed he “was able to get the window and outside screen open, climb to a lower roof and jump to the ground or parking lot at the rear of the hospital.”

Two weeks later, Multaler was picked up by FBI agents in Mississippi and returned to Wisconsin. By 1973, Multaler was back on the streets, again tallying traffic violations, like speeding and driving with a revoked license.

In July 1973, Multaler and six others were arrested in a counterfeit money ring operating out of Fond du Lac. Fake bills had been circulating in the area that summer, and federal agents silently traced them back to their source.

When Secret Service agents raided Multaler’s Waupun apartment, they found a small press, printing supplies, and about $200,000 in counterfeit bills—many of which had been soaked in coffee to lend them a weathered appearance. Agents located Multaler at work, where he painted cars, and took him to Waukesha County Jail, where he was held on a $5,000 bond. When Multaler was arrested, he had approximately $2,500 in fake bills on his person.

While in custody, Multaler told investigators he had learned the art of printing while in prison at Green Bay, where he had served time for his gun charge in 1968. Multaler initially pleaded not guilty to manufacturing counterfeit currency, but in early 1974, he changed his plea to guilty and was given five years of probation.

Multaler was still on probation when he was arrested for the attempted highway kidnapping of the young woman in June 1975. After his arrest, it didn’t take long for investigators looking into Multaler’s background to count him as a possible suspect in the still-unsolved murders of Sherry Moriarity, Wendy Brown, Cynthia Franckowiak, and Susan Wicinski (these four cases had garnered the most media attention, but the murders of Linda Frank and Stena Weber also appeared to be unsolved).

Multaler was a plausible person of interest. He had a rap sheet dating back to 1968—including the attempted robbery of the two hitchhikers—and most of the murdered women were thought to have been killed in or near their vehicles. Then there was a peculiar incident: Milwaukee County District Attorney Edward Michael McCann received an anonymous newspaper clipping about the 1975 abduction attempt with a handwritten note reading, “This man is the South Side Killer (7 Mile Rd.)[.] He has raped 36 girls.”

A handwriting analysis of the note pointed to Multaler, prompting investigators to dig even deeper into the man’s background. Detectives interviewed Multaler’s ex-girlfriend, who reported that while making love, he sometimes “placed both his hands around her throat and choked her,” occasionally to the point that it was difficult for her to recover. Much of the information gleaned from this woman would make its way into the affidavit used to search Multaler’s home decades later.

She also revealed that Multaler kept a scrapbook of newspaper clippings centered on the murdered Milwaukee women. One scrapbook, she said, even included clippings from another murder case, though she didn’t specify the victim. The scrapbooks and clippings would later prompt Multaler’s own defense attorney to conclude that his client had a “fairly unusual interest in these cases.”

In January 1976, Multaler pleaded guilty to four counts related to the attempted kidnapping of the woman in June 1975. In admitting his guilt, Multaler came under more intense scrutiny for the open Milwaukee murders. When detectives interviewed Multaler in March 1976, he denied any involvement in the killings, saying he would take a sodium pentothal test—a truth serum—to confirm his innocence.

“You may use any and all evidence as you see fit or as needed in reference to these four murders,” Multaler wrote in a letter, against the wishes of his defense attorney.

Authorities didn’t take Multaler up on the offer. After his kidnapping conviction, in May 1976, Multaler was incarcerated in Central State Hospital by Judge Christ T. Seraphim, who called the convict “the most dangerous man that has ever been before me in my 16 years on the bench.”

Multaler agreed, acknowledging that he himself didn’t think it was a good idea for him to “be out” thanks to his violent tendencies. Multaler confessed that he had attacked other women as he did the driver in June 1975, and had planned to sexually assault her if the abduction had gone according to plan.

“I have done it several times, your honor, over the period of years that I have been free outside,” Multaler said. “I have a long prison history and the sex life that I do have is inadequate. I have gone out and done it since I have been approximately 13.”

Despite his rambling confessions and apparent mental illness, investigators couldn’t definitively tie Multaler to the unsolved murders. He admitted to being a violent predator, but never provided the specifics that would connect him to the killings.

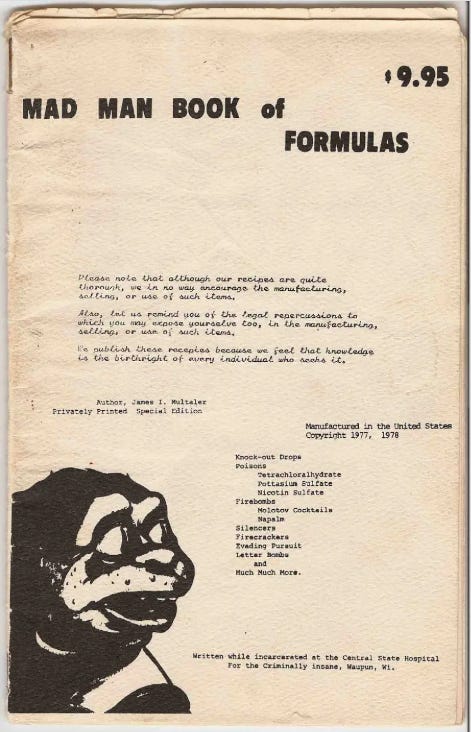

While at Central State Hospital in Waupun, Multaler began his next printing project: an unusual 22-page booklet called “Mad Man Book of Formulas.”

Inside, readers found recipes and step-by-step instructions on how to make “little goodies like poisons,” napalm, laughing gas, and “knockout drops” made from toilet cleaning chemicals. The self-published booklet was a survival guide for suspicious DIY activities. It was advertised for $9.95 in the classified sections of magazines like “Soldier of Fortune.”

Multaler began publishing it shortly after entering Central State Hospital, and by 1982, he had supposedly sold more than 3,000 copies. The operation was shut down when a hospital employee came across one of Multaler’s magazine ads. That same year, Multaler requested a release from the state hospital, claiming he was no longer mentally ill. His appeal was swiftly denied.

In the meantime, investigators continued looking into Multaler’s connections to the women murdered outside Milwaukee, but couldn’t organize enough evidence to bring charges against him. For years, the cases stalled, and Multaler served out his sentence at the state’s criminal hospital.

By the fall of 1988, Multaler was back in the general public, but he was once again arrested—this time charged with second-degree sexual assault. Investigators, including Lt. James Ivanoski of Racine County Sheriff’s Department, began to revisit Multaler as a suspect in the 1970s murders—what were now cold cases.

As Ivanoski reviewed old case files, he focused on a handful of overlooked details that seemed to conclusively link Multaler to at least one of the victims: 15-year-old Wendy Brown. According to police reports from 1976, Multaler admitted that on the night Wendy disappeared, he picked up the young hitchhiker and brought her to a drive-in restaurant—the same one where she was supposed to meet a friend.

At one point, when pressed for details about that day, Multaler claimed to have “had a drug-induced flashback and so couldn’t remember anything other than stopping there.” It was a perplexing alibi, but since he confessed to being one of the last people to see Wendy alive, Multaler had definitively tied himself to at least one of the Milwaukee victims. Why these threads hadn’t been pursued more in the 1970s was unknown.

In November 1988, Ivanoski pushed for Multaler to take a polygraph or “truth serum” test, but Racine County District Attorney Lennie Weber acknowledged that the results of either test would be inadmissible in court. Despite his tentative connection to one of the victims, Multaler wasn’t arrested or charged for the murder of Wendy or the other women. Their cases remained unsolved through the 1980s and ‘90s.

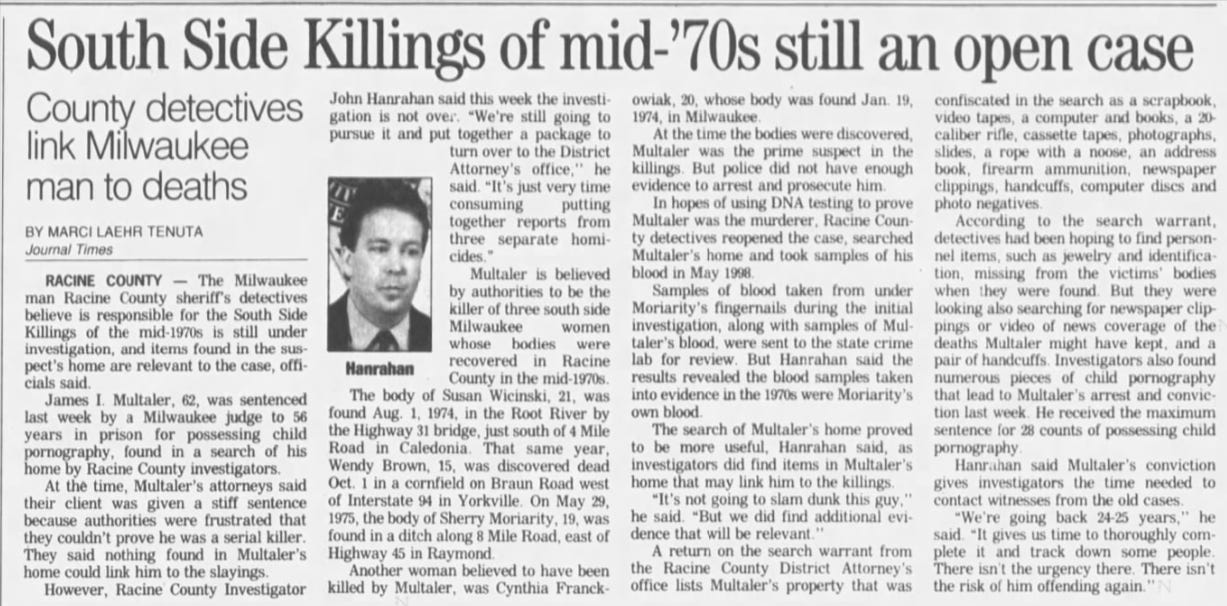

Then, in May 1998—a decade after he was last arrested for sexual assault—Multaler became a suspect in the February 1997 murder of a woman in a Racine nature preserve. Multaler would eventually be cleared of the crime—he was in poor physical health by this time— but detectives, including Racine County Investigator John C. Hanrahan, decided to once again look into Multaler’s links to the ‘70s cold case murders.

Like Ivanoski, Hanrahan found more connections that firmly pointed to Multaler as the common denominator in at least two of the murders. Not only did the initial investigation reveal that Multaler had seen Wendy the night she disappeared, but when Multaler admitted to picking her up, he also “corrected” information about the teenager that was inaccurate in her missing person’s report.

Although he initially claimed to not know what happened that night, when asked during a separate interview if he was involved in her disappearance, Multaler had admitted that he may have been.

“If she is dead I must have killed her,” Multaler reportedly said, according to court documents. “I had to kill her, I don’t recall.”

He didn’t get all the facts straight, though. When asked to describe Wendy’s clothing, Multaler detailed a specific outfit, but it wasn’t Wendy’s. Instead, it was exactly what Susan Wicinski wore when her body was found in August 1974.

When Multaler had been taken to the state hospital in 1976, reports claimed, he also admitted that he “always liked strangling—playacting—with every girl [he had] known,” a habit confirmed by his ex-girlfriend. It was at this time that doctors at the institution diagnosed him as having antisocial personality disorder, “moderate unspecified sexual deviation,” and other mental health conditions.

His case file also revealed that in 1978, Multaler contacted a Milwaukee television station to request copies of any stories related to the murders of the women in 1974 and 1975—presumably for the scrapbook his ex-girlfriend reported finding in his home.

Multaler had a more tentative connection to Cynthia Franckowiak, who was found with a note in her pocket that read “James McDonald.” The name may have been an alias for Multaler, whose ex-girlfriend reported seeing the same moniker written down somewhere in his home during her stay there in 1975.

In 1988, when Multaler was arrested for sexual assault, the investigation also revealed that his 13-year-old daughter admitted to police that her father had sexually abused her over the course of many years.

Looking back, Hanrahan also noted a striking pattern: the murders stopped abruptly in 1976—the year Multaler was imprisoned.

Years worth of case files and circumstantial evidence pointed to Multaler as the serial murderer of the young Milwaukee women, yet multiple detectives—across decades—couldn’t build a strong enough case to charge him.

To Hanrahan, the connections were more than enough to pin the murders on Multaler. Now, he just needed physical evidence. In May 1998, Hanrahan filed an affidavit requesting a search warrant of Multaler’s Milwaukee home, where he lived with his wife and daughter.

Hanrahan knew that Multaler had owned the house for twenty-odd years, and he believed that if Multaler was the killer, he likely kept possession of some of the murdered women’s things as mementos. He hoped to find Wendy’s Mickey Mouse watch and bracelet, Sherry’s gold earring and pendant necklace, and Susan’s pin.

In the affidavit, Hanrahan attempted to prove “the reasonable inference that he [Multaler] would be likely to retain the mementos more than 20 years after the murders,” the way many serial killers often do. The affidavit was convincing, and in May 1998, authorities received permission to search Multaler’s home.

The search was productive, but not for reasons investigators predicted. When they combed through Multaler’s residence, police retrieved some evidence potentially related to the serial murders, but they also found something else: illegal images of children. When investigators searched the contents of two computer disks, they found 79 explicit photographs of minors—material Multaler said he possessed for “possible resale” or to create similar content himself.

Multaler faced 79 charges, each carrying a potential two-year sentence. Held at Milwaukee County Jail pending a preliminary hearing, Multaler argued that the charges were duplicative and should be reduced to two counts—one for each disk. The court rejected his argument, and Multaler ultimately accepted a plea deal that resulted in a 56-year prison sentence.

Investigators later revealed that the search of Multaler’s home didn’t uncover any direct links to the murders of the Milwaukee women, but they did seize several circumstantial items, including scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, videotapes, and a pair of handcuffs.

They also took a DNA sample from Multaler to see if it matched evidence found under Sherry Moriarity’s fingernails, but the blood sample was determined to be her own. By the summer of 1999, investigators were no closer to connecting Multaler—then 62 and serving his lengthy prison sentence—to the Milwaukee murders.

For years, Multaler appealed his convictions, arguing that the search warrant and sentencing were unjustified. In 2002, Wisconsin’s Supreme Court ruled that the search warrant was legal and that Multaler’s sentence would be upheld. With his legal maneuvering exhausted, Multaler accepted his fate as an inmate of Dodge Correctional Institution in Waupun.

In February 2004, Multaler died while in prison. Despite years of separate investigations, authorities in Racine and Milwaukee Counties were never able to bring charges against him for the murders of Sherry Moriarity, Cynthia Franckowiak, Susan Wicinski, Wendy Brown, Linda Frank, or Stena Weber. Their murders remain officially unsolved to this day.

Fascinating case!

Check my newest story out https://substack.com/@skiptracingandmystery/note/p-179871108?r=3nlwlw&utm_source=notes-share-action&utm_medium=web