The Murder of Rose Twells

It would take decades for authorities to discover who killed a "first lady of the community" just days before Christmas 1979.

On December 20, 1979, Charles Edgecumbe pulled on his coat and trudged across the snow-swept street toward the home of Rose Twells in Woodbury, New Jersey. Charles was married to Celeste, Rose’s niece, and was coming to bring the 86-year-old woman over for dinner at the Edgecumbe residence.

Most Thursdays, Rose and Celeste went shopping in town. Rose, a widow who lived alone in a 140-year-old mansion, was fiercely independent, but allowed Celeste to take her shopping for groceries each week.

On Tuesday, December 18, Rose had cancelled their usual Thursday trip, but accepted a dinner invitation in its place. When Charles arrived at Rose’s door just after 5 p.m. on Thursday, he knocked and received no answer. He continued knocking, and waiting, and when there was still no sign of movement inside, Charles headed home to retrieve a key to Rose’s front door.

When he entered the white, three-story stucco house, he found the home in disarray. Rose had always kept antiques and collectibles organized around the house, but on this late afternoon, rooms were disheveled, and items were scattered haphazardly. When he entered the living room, Charles saw something that would haunt the city of Woodbury for decades to come.

The living room was ransacked. Furniture lay overturned and antiques were strewn about. At the bottom of the staircase, Rose Twells lay motionless, ankles bound by a lamp’s electrical cord. The cord was tied to a stairwell banister, and a pool of blood appeared beneath her head.

Charles ran home across Delaware Street and called the police. In shock, he told them that Rose Twells, the retired teacher who had always been active in their tight-knit community, was dead. The murder made no sense to Charles or Celeste, and for decades, it would remain Woodbury’s most elusive cold case.

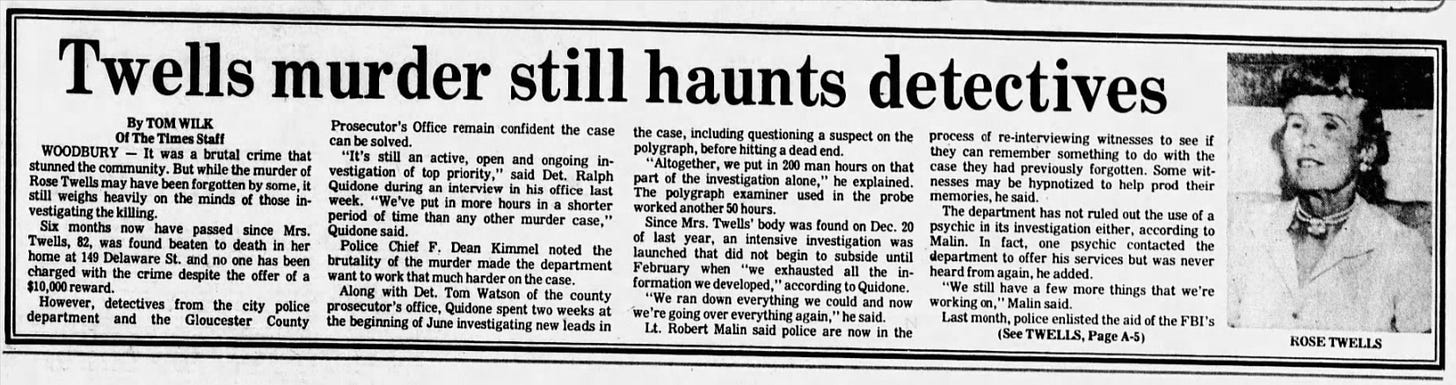

At the time of her death, Rose Twells was something of a reclusive woman, but that had not always been the case. Rose had been married to John Stokes Twells, who had served as Woodbury’s mayor in the 1930s. Rose had been a strong presence beside her husband, who was hard of hearing.

She took care of John in countless ways, and would often “yell at the top of her lungs” to make sure he could hear, said one neighbor. John, in turn, appreciated Rose: every May Day, he never failed to send a bouquet of spring flowers, said the local florist.

For 15 years, Rose taught at Mantua Grove School in West Deptford Township. She and John had no children, but she enjoyed the company of young people and many considered her an excellent teacher. Her family had deep roots in the area, dating back to before the Revolutionary War. Rose was a descendant of Caesar Rodney, a founding father who had signed the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776.

For years, the Twells were a well-known couple in the community. Rose was a member of the Presbyterian Church and volunteered with the local Red Cross and Woodbury Women’s Club. John was a staple of town politics, and when he died in 1970, Rose became a widow who didn’t want to leave behind her opulent house on Delaware Street.

Despite friends and family—including Celeste Edgecumbe—insisting that she not live by herself, Rose had remained stubbornly independent throughout her 80s. After John died, she kept her home clean, though full of antiques and mementos. “The whole house was like stepping back into the 1930s,” said a retired detective in 2005.

In 1976, Rose donated three acres of land across the street to the city of Woodbury, which in turn converted the acreage into a bird and wildlife sanctuary in memory of her husband, who was one of the town’s earliest council members.

When summer would arrive in Woodbury, Rose tended to her garden in the morning and evening, working among her favorite flowers and plants. And when winter hit, Rose—afraid that the old oil system in her home would malfunction—kept her house barely warmed.

When police arrived to investigate Rose’s death on December 20, the thermostat in her home was set in the 40s. She was dressed in enough layers to suggest that this was her regular winter routine.

Rose would go on frequent walks into downtown Woodbury and was often spotted around town as she went about her business. On Tuesday, when Celeste last talked to her aunt, Rose was seen walking in Woodbury’s shopping district. City Clerk David Phillips saw Rose when she came in to pay her property tax bill that day.

The frail widow, described as an “elegant lady,” stood less than five feet tall and weighed no more than 90 pounds, yet still walked in every season to complete her errands as needed. To those who knew her, Rose was small but mighty.

One person was particularly shocked by Rose’s murder: current Woodbury mayor Frederick Bayer. As two political-minded families in town, the Bayers and Twells knew each other well. Fred phoned and visited Rose often, checking up on the woman he and his 17-year-old son, Jeffrey, had come to know, affectionately, as “Aunt Rose.” Fred’s mother had met Rose when the two women attended Trenton State Teachers College in the 1920s. There, they began a friendship that connected the two families more than 50 years later.

“She was a very friendly woman, extremely interested in the city,” said Fred, after Rose’s death. “She always looked at you as the boy next door, you never grew up in her eyes. But it’s nice to know that some people think that way.”

In the months before Rose’s death, several thefts and other petty crimes began to crop up in Woodbury—particularly on Delaware Street, which ran east-to-west through the heart of town. In Rose’s area, some elderly residents had begun to fear for their safety while walking around town.

An elderly woman who lived near Rose was mugged while walking back from downtown in recent weeks, and according to Woodbury Police Chief F. Dean Kimmel, there had been three purse snatchings, an assault, a case of breaking and entering, and an armed robbery in the weeks leading up to Rose’s death. About a block away from Rose’s home, a juvenile had recently been arrested for attempted burglary. There had been two robbery attempts of a local flower shop in November.

The crime wave was out of the ordinary for a city like Woodbury, and it was enough to spur police to set up stakeouts on Delaware Street in early December. By December 7, however, police hadn’t witnessed any additional crime in the area, so they concluded the four-day operation.

Despite the uptick in recent crimes, Woodbury—and Rose, herself—had seen similar cases come and go. Two years before her death, Rose was visiting family in California when someone broke into her home through the cellar door. It didn’t appear as if anything had been stolen, police concluded, but the nature of Rose’s antique collection made it difficult to be sure.

When Woodbury police arrived at Rose’s home on December 20, they found no signs of forced entry. The back door was unlocked, which Celeste and Charles noted was unusual. It had been snowing on the day Rose was found, so any tracks coming in or out of the home had been covered. The temperature of the house had preserved the crime scene well, examiners noticed, and investigators located several blood-covered items in the living room.

It wasn’t clear what had been used to kill Rose. An examination of her body revealed that her only injuries were to her head, likely done with a blunt, heavy object. Deputy county medical examiner Dr. John W. Holdcraft estimated that Rose had been killed Tuesday night, though it would take an autopsy to uncover specific and accurate details about her death.

As it stood, police knew they had a homicide on their hands, but it wasn’t clear what the motive of the crime was. Because Rose’s home was so packed with items, it also wasn’t initially clear if anything was missing from the home. It would take investigators days to canvas the house completely, and even then, police were never able to catalog all the items in the house before and after Rose’s death.

“One of the problems we have to overcome is that she was a ‘saver,’” said Woodbury Detective Lt. Robert Malin. “It looks like she saved everything. It’s going to be a long time before we’re able to find out if anything is really missing.”

Because of the ransacked nature of the house, Captain Donald Layton of the Gloucester County Prosecutor’s Office believed it was a burglary gone wrong. The intruders may have been looking for cash or items to sell, he guessed.

Whatever theories the police had about Rose’s killer, they could not be confirmed by witnesses. That week, a cold spell meant that most families were safely and warmly in their homes before dark each afternoon. And that week’s snowfall meant that there were no footprints preserved in or around the home. What made Rose’s death so difficult to solve was that it occurred in the cold, solitary vacuum of a New Jersey winter.

With results from the autopsy days later—one that showed “nothing too unexpected”—Woodbury investigators believed Rose had died 15 to 20 hours before Charles found her. The examination also revealed that she had confronted her assailant, fighting back as much as her 85-pound frame could manage. City police and the Camden County Prosecutor’s Office had no suspects, clues, or motives after five full days of investigating the Twells’ home.

Police hoped that a reward of up to $7,500 for information related to the crime would spur leads, but it resulted in sparse calls and no substantial insights.

Six days after Rose’s body was found—one day after Christmas—60 friends and family arrived at Woodbury’s Presbyterian Church to remember the life of Rose Twells, whom her reverend called the “first lady of the community.” Police attended the funeral and took photos of those in attendance, hoping the killer would show up in a strange sort of reverie.

Rose was buried at Eglington Cemetery alongside her husband. The official date of death on her gravestone read December 19, 1979.

Six months after Rose’s death, Woodbury police had yet to make an arrest in her case. That wasn’t for a lack of trying: Detective Ralph Quidone said the department “put in more hours in a shorter period of time than any other murder case.” By Quidone’s estimate, investigators had poured 200 hours into Rose’s case and were still no closer to any answers by June 1980.

Some of the challenges remained the same: after interviewing Rose’s neighbors, it was clear that the snow and weather that week prevented there from being any eyewitnesses. Inside the house, the condition of Rose’s home—full of old antiques and curiosities—made it difficult to obtain fingerprints thanks to the amount of dust on nearly every surface.

Still, Woodbury police had conducted plenty of interviews and had even given polygraph tests to 12 to 15 people, though none led to arrests. After half a year of no answers, investigators were open to anything, including working with a psychic or hypnotist to help retrieve information through unconventional means.

More traditionally, they enlisted the help of the FBI’s Criminal Personality Profiling program, based in Quantico, Virginia. Woodbury investigators hoped that the FBI’s expansive knowledge of criminal profiles might help them find evidence or characteristics of the homicide that they had perhaps overlooked.

By the summer of 1980, detectives had ruled out 40 suspects. Rose’s case file was more than a foot thick, but they were no closer to a legitimate perpetrator or motive. They also weren’t entirely sure of what was taken from the home when Rose was killed, if anything, but believed the murder weapon may have been removed as the assailant, or assailants, escaped.

Two years after Rose’s murder, the Woodbury Old-City Restoration Committee wanted to pay tribute to the Twells by hosting their second annual designer’s showplace in the couple’s empty home. It was perhaps a macabre suggestion, and one that eventually fell through after a pipe burst and became irreparable before the event. At the time, in January 1981, Woodbury Police Chief Kimmel stated that there had been no new leads in Rose’s case, although investigators held weekly meetings to review their progress.

Years passed with no public updates on Rose’s murder. By the mid-1980s, the Twells’ home was rezoned as a professional office building, and whispers of her unsolved murder became fewer and farther between. Police continued to follow up on new leads, but those, too, had dwindled in recent years.

In December 1986, the Gloucester County Times ran a profile on the seventh anniversary of Rose’s death. It recounted the circumstances—that Rose had been killed just days before Christmas, when she planned to join her nephew, Thomas Twells, for a family holiday near Baltimore. Thomas had been responsible for the reward offered for leads on Rose’s case, though the offer came and went without success.

Despite the passage of time, the paper reported, detectives were still committed to solving Rose’s murder. Detective Quidone, who was on the original case in 1979, was still protective of the information police had on hand, and prevented reporters from reviewing their files. Police still wouldn’t publicly reveal what the murder weapon had been, though at least four years had passed since they had received a legitimate lead. With each passing year, Rose’s case grew colder, but Woodbury police were determined not to give up.

Quidone said that from time to time, the department—and even the medical examiner—would review Rose’s case file to see if there was anything they had overlooked the first time around. “Maybe there’s something in there we missed because it’s so obvious you go right over it,” Quidone said. “But I don’t think that’s the case.”

For Celeste Edgecumbe, the answer was in plain sight. “I think it was a local person,” she said in December 1986. “She always kept the doors bolted so tightly shut.” Because there was no sign of forced entry, and Rose was so particular about who she let into her home, Celeste believed that whoever killed her aunt was intimately familiar with Rose and her routines.

In 1986, investigators noted that one item in Rose’s home had never been found: a two- to three-carat diamond pendant. The diamond, valued at $10,000, had originally come from a ring, but had been reset into a white-gold Tiffany setting. The missing jewelry and disheveled condition of the home led police to further conclude that Rose’s murder was the unfortunate result of a burglary.

With leads exhausted, Quidone’s optimism centered on one hope: that the passage of time would work to investigators’ favor. “We’re hoping that sooner or later the killer will mention it to someone,” he said. “We’re always hopeful.”

In 1990, Celeste’s hunch that a local man murdered Rose Twells gained steam. It had been 11 years, but the Twells family—and others in Woodbury—were sure that those responsible for Rose’s death were heading, however slowly, toward justice.

“There’s a lot of evidence,” Thomas Twells told reporters. “I can’t believe that anybody in a relatively obscure town in South Jersey can squash a murder investigation or keep evidence from coming to light.”

The Twells wouldn’t publicly name the suspect they had in mind, but newspaper reports called him “a young man who is the son of a Woodbury family.” As police worked their investigation, Thomas began looking for a private investigator—ideally, a retired FBI agent, he said—who could help the family piece together what had eluded authorities for more than a decade.

The Twells family believed that this young man had a key to Rose’s home and knew she would have jewelry and cash in her possession. They claimed to have found a bloodied jewelry box in an upstairs room after the police’s initial investigation, suggesting that detectives weren’t as meticulous as they appeared to be. The family also suggested a brooch had been stolen from Rose’s home, retrieved, and given back to police, though Detective Quidone said this was inaccurate.

The rumored suspect was no stranger to Woodbury police. “Yeah, it’s the hot rumor all over town,” said Norman Reeves, deputy chief of the Gloucester County Prosecutor’s Office. But without hard evidence, Reeves confirmed, the county couldn’t make a good arrest—or a case for murder.

On June 21, 2003, the Gloucester County Times ran a front-page story with the headline: “Three charged in 23-year-old murder.” The story featured photos of Rose Twells, the crime scene, and the fresh mugshots of two individuals: Clifford Jeffrey and Jeffrey Bayer.

It had been 13 years since the Twells suggested they knew who was responsible for Rose’s death, and now, police finally had enough evidence to make their arrests—three in total, and all already in jail or prison.

Jeffrey, 41, was serving time at South Woods State Prison for various drug convictions. Bayer, 39, was scheduled to be released from South Woods after serving five years for burglary and theft convictions. Mark English, 41, was being held on grand theft charges at Florida’s Madison Correctional Institute. In Rose’s case, all three men faced charges of first-degree murder, first-degree felony murder, and first-degree conspiracy to commit murder.

The “young man” from a Woodbury family that the Twells had long suspected was Jeffrey Bayer—the son of former Woodbury mayor Fred Bayer, who was in office in 1979 when Rose was killed. Fred may have been a close friend of the Twells, but Jeffrey, 17 at the time of Rose’s murder, was a known delinquent in town.

In the spring of 1979, Janet Bayer, Jeffrey’s mother, had thrown him out of the house after he stole dinner silverware to pawn for drug money. He also burglarized another home in the community, but Janet was able to trace the jewelry back to a pawn shop and retrieve it. Considering the condition of Rose’s home—and now, with Bayer’s criminal history coming to light—investigators were confident that Bayer and his accomplices meant to rob Rose the week before Christmas.

The 2003 arrests of Bayer, English, and Jeffrey were the result of information Woodbury police received back in 1991, when an anonymous source came forward with details of the crime. The informant was given immunity in exchange for a full testimony of what happened to Rose Twells.

The informant revealed that she had been part of a group of teenagers who were, in December 1979, plotting to rob Rose, focusing on cash and jewelry that they could later pawn. The informant claimed that the group of teens included Bayer, English, and Jeffrey, who were all known to be in the same social circles.

By 2002, authorities had corroborated insights from the informant and other sources, motivating Woodbury detectives, including Robert Atkisson Jr., to bring the case to a close. Atkisson was a rookie in 1979 and now had 23 years on the job—23 years spent investigating Rose’s case.

“Within the last year, it really got hot,” said Woodbury Police Chief Reed Merinuk, who was just 11 years old when Rose was murdered. “We were getting good information and corroboration. They were relentless. Every time they got a little more information, they jumped right on it.”

After years of roadblocks, Woodbury’s only unsolved murder case appeared close to being solved.

Prosecutors soon discovered that the charges against Bayer would be problematic. To start, he had been a juvenile at the time the crime was committed. His public defender, Jeffrey Winter, citing the laws in place in 1979, argued for Bayer to be tried as a juvenile. English, who was scheduled to face a separate trial, was also a juvenile at the time.

The prosecution argued that Bayer’s lengthy criminal history, dating back to the 1970s, was sufficient to have him tried as an adult. In February 2004, Bayer and Jeffrey were indicted for murder charges; a judge ruled that both would indeed be tried as adults.

As Bayer’s trial loomed, the informant who broke open the case was revealed to be Luanne Waller, Bayer’s girlfriend at the time of the murder. Waller offered firsthand accounts of her conversations with Bayer about Rose back in 1979, and she had even been at the scene on the night Rose was killed. According to Waller’s account of the botched robbery, she acted as a lookout as Bayer and his accomplices entered Rose’s home. “I can’t forget about what happened,” she said in a taped interview with police.

After the murder, Waller stayed quiet out of fear of Bayer’s retaliation, she claimed. She moved away, but when she came back to Woodbury in the early 1990s, Waller began dating a police cadet. When he revealed that Rose’s murder was still unsolved all these years later, Waller finally revealed what she had known all along. Waller claimed that she was surprised the murder case hadn’t been resolved by then, so she went to the police, hoping for the immunity she was eventually granted.

In October 2004, Mark English was also indicted on murder charges. All three defendants were scheduled to face trial in 2005, with Bayer going to court first. In April, Bayer refused any last-minute plea bargains, confirming that his case would go to trial.

There, his defense focused on a lack of tangible evidence. But while there was no physical connection to tie Bayer to the scene—police had never recovered DNA traces belonging to him—several witnesses claimed Bayer had told them about the murder in the weeks and months to follow.

Waller was the prosecution’s key witness, but another friend, Steve Forbes, testified that he had given Bayer and English a ride into Philadelphia after the murder so that they could pawn stolen jewelry. Justine Shenkus, who was 13 at the time of the crime, reported that Bayer said he killed Rose after she caught him trying to steal things from her home.

A woman named Shirley Logan also testified that she had overheard Bayer confess to the murder. Several days after the crime, Logan said, she had received an anonymous phone call from someone who said Shirley would be killed if she talked to the police.

In each case, the witnesses had stayed silent for so long because they feared Bayer’s retribution. Bayer’s defense, on the other hand, presented these witnesses as unreliable—biased by the passage of time and drug-riddled memories. In the defense’s view, these witnesses were problematic because they couldn’t accurately recall what they did as teenagers decades ago.

When jurors were asked at the beginning of the trial if they were capable of convicting someone of first-degree murder with no physical evidence, all 15 jurors said, unequivocally, that they could not. This seemed like a win for Bayer’s defense, but as the trial unfolded, he did himself no favors. When he was called to testify, Bayer admitted to using drugs as a teenager, and made derogatory statements about others, including Waller, his former girlfriend.

Curiously, he also said that he didn’t know Rose Twells, Mark English, or Clifford Jeffrey at the time of the murder—despite years of relationships between the Twells and Bayer households. He claimed not to have met Waller until 1981 or 1982, despite her own testimony. Bayer’s time on the stand proved that he was interested in distancing himself from the crime and those involved, regardless of other witness testimonies.

During the trial, Logan, who was Clifford Jeffrey’s 16-year-old girlfriend at the time of the murder, claimed that Bayer was focused on finding Rose’s large diamond. Shirley said Bayer believed it to be a “10-carat diamond ring,” though the pendant that went missing was two to three carats in size.

Perhaps most convincing was Waller’s account of the murder. She testified that on December 20, she finished her homework, left her parents’ house, and joined Bayer and his friends. They went to Rose’s home, and the men went inside, Waller said.

When one came out 25 minutes later, he “looked scared.” Rose left shortly after, and Bayer called her that night to recount what happened. What was supposed to be a quick, easy robbery for drug money turned violent almost immediately.

Bayer said that Rose “must have heard somebody in the house,” Luanne testified. “She had recognized Jeff and was going to call his dad. Jeff grabbed her and she fell down the steps and he hit her in the head.”

On May 27, 2005, after five days of witness testimony, it took less than three hours for a jury of nine women and three men to find Bayer guilty of felony murder. He was acquitted of the first-degree murder charge, as the jury could not tell without a reasonable doubt that he was the one who actually killed Rose. They all agreed, however, that he had participated in the burglary-turned-murder.

Thomas Twells, Rose’s nephew who had set up the reward for her case in 1979, was present during the announcement of the verdict. “I’d hate to have anybody take my blood pressure right now,” Tom, 70, said. “It’s through the roof, but it’s coming back down.”

Because of the amount of time that had passed since Rose’s murder, Bayer was sentenced under New Jersey’s 1979 murder statutes. The judge sentenced him to 30 years in prison, with parole eligibility after 15 years. Had he committed the crime after New Jersey updated its laws in the 1980s, Bayer could have faced a more extended prison sentence because of his prior convictions for burglary and theft.

In August 2005, Clifford Jeffrey pleaded guilty to felony murder, but attempted to recant after English’s case resulted in a mistrial in October 2005. A judge affirmed the plea deal in November 2005, however, and Jeffrey’s conviction was upheld. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

In February 2006, a jury in English’s second trial acquitted him of murder charges. He did plead guilty to another crime, however, stemming from an assault on a sheriff’s officer in January 2005.

For his time in custody, Bayer was credited with 756 days of time served and more than 4,000 days of “gap time” credit. In June 2008, a three-judge panel upheld Bayer’s conviction after his defense team appealed, claiming that the jury in his trial overheard “damaging and prejudicial information about the defendant.”

In June 2018, 13 years after he was convicted of Rose Twells’ murder, Bayer was released from New Jersey State Prison.

Very nice article. I really felt like I got to know "Aunt Rose." What a senseless crime.