The Abduction and Murder of Tara Sidarovich

When a teenager went missing after a routine home maintenance appointment, her family's search for answers lasted more than a decade.

In the summer of 2001, Sharon and Keith McPhillips moved from Scranton, Pennsylvania, to southwest Florida with Sharon’s three children: 19-year-old Tara, 13-year-old Veronica, and their younger brother, Paul.

The family chose sunny Punta Gorda for its low crime rate and ideal weather. They rented a quaint home in the Tee Green neighborhood east of town, and didn’t take long to settle into a new routine punctuated by “family day” Sundays.

Each week ended the same way: the family of five spent the entire day together, running errands, shopping, and exploring what their new town had to offer.

On Sunday, September 30, 2001, their itinerary included breakfast at Cracker Barrel, a trip to a Fort Myers flea market, and a casual stroll around Port Charlotte Town Center mall after catching Keanu Reeves’ Hardball. The mall was a familiar hangout for Tara, who had recently begun working at a jewelry kiosk there.

Florida was growing on Tara, but that hadn’t always been the case. She had resisted the move at first, refusing to leave her friends and the Northeast community she’d grown up in.

But just three weeks after the rest of the family headed south, Tara followed suit. She made plans to attend Fort Myers’ Edison Community College, where she wanted to learn to become a crime scene investigator.

After another family day together, Sharon’s household began Monday, October 1, like any other weekday morning. Veronica and Paul went to school. Sharon and Keith each drove to work.

Tara had plans to pick up her paycheck from Golden Isle Jewelers, but first had to wait for a septic company to stop by and inspect their septic system. Heavy rains over the past few days had caused septic problems throughout the neighborhood, and several homes had reported backed up tanks.

Just before noon, Tara called a coworker to confirm she’d stop by the mall later to grab her check. Sometime after noon, two men from ABC Septic arrived: Phillip Barr, the company’s owner, and David McMannis, a part-time employee.

The men entered the home, inspected a toilet, and assessed the home’s septic system. Toward the end of the appointment, the men backed their truck up to the house.

After some time, they left.

When Veronica stepped off the school bus just before 4 p.m. that Monday, she felt a sense of relief. She had left her keys at home that morning, but now, seeing Tara’s car still in their driveway, Veronica knew that she and Paul could get into the house without issue.

But when Veronica and Paul reached the front door, something felt off. The door wasn’t closed all the way, and when she stepped inside, Veronica noticed some items had been moved—subtly, perhaps, but moved nonetheless.

When Veronica called for Tara, she received no reply. Veronica walked through the home, continuing to call for her older sister, but soon realized Tara was not at home. Despite her car being in the driveway—and her purse and keys still in the sisters’ shared bedroom—Tara was gone.

Veronica knew immediately that something had happened. Her sister wouldn’t leave without telling anyone, and she certainly wouldn’t leave without her purse and personal items.

Tara, who was once named to the “Who’s Who Among American High School Students” list, was responsible and communicative. Her absence struck a note of distress that Veronica couldn’t shake.

When Keith arrived home shortly after Veronica, he shared her unease about Tara’s absence. Keith and Tara were close, and like Veronica, he knew Tara wouldn’t leave without mentioning it to someone in the family. Tara, who paid room and board at their new home, was like another dependable parental figure in the house, especially to Veronica.

Keith quickly called Sharon, who tore through her 40-minute commute home. He next called the Charlotte County Sheriff’s Office, and when Sharon arrived at the house, an officer was already on the scene.

Sharon, Keith, and Veronica voiced their concerns to the officer, who was focused on cataloging what appeared to be a burglary. Jewelry and cash were missing, and the officer seemed more concerned with this information than with Tara’s whereabouts.

The scene did appear to be a burglary. When Keith had arrived home, he noticed that a television set on top of his bedroom dresser was facing forward, not the direction it usually faced for someone lying on the bed nearby, watching TV. Jewelry and cash in the vicinity were gone. There also appeared to be scuff marks on the dresser, as if someone had kicked it with the bottom of their shoe.

Throughout their home, Keith and Sharon found small, subtle signs that something had occurred in the house that afternoon. When friends came over to help look for Tara, someone noticed an earring embedded deep in the home’s carpet. Then another. And another. Tara had been wearing all three that morning. Dirty boot prints marked various parts of the carpet.

Outside, the family noticed other odd details. A small palm tree had been knocked over, its decorative border smashed into the lawn. Hair ribbons that Tara had been wearing lay in the yard. Tire tracks ran the width of the front yard and appeared to go directly up to the front door. For what reason, Sharon and Keith didn’t know.

As more of the scene’s details unfolded before the family, the more they feared the worse: that Tara had been abducted.

The officer on the scene suggested Tara had perhaps gone to a friend’s house or a football game taking place nearby. It was also suggested, at various points, that she may have been a runaway. Because Tara was 19 and technically an adult, the officer could put out a BOLO—a be-on-the-lookout notice—but 24 hours would have to pass before she could be declared officially missing.

“I get very angry with the way it went in the beginning,” Keith would say years later.

Sharon and Keith knew Tara better, and they didn’t wait: the couple began their search for Tara immediately. They didn’t care about the cash or the jewelry missing, though Keith would later admit that one of the pieces taken was a “dad” ring Tara had given him—something he cherished as a father figure in the young woman’s life.

She had gone by Tara Ord in high school, but afterward took the last name of her biological father, John Sidarovich (in some accounts, she appears as Tara Ord-Sidarovich). After years in the same household, Keith and Tara had grown close, and he viewed her as a “buddy,” he would say later, tearfully.

When Sharon and Keith learned that Tara never showed up to collect her paycheck at the mall that day, they knew with absolute certainty. She had been taken.

On Tuesday, October 2, Tara was officially declared a missing person. By then, however, the crime scene—what appeared to be the entire McPhillips residence—was no longer pristine.

Dozens of people had been in and out of the house since Monday afternoon, helping with the unofficial search for Tara. When crime scene investigators arrived at the house on Tuesday, they faced a scene that had not been well-preserved. Still, they went to work.

The crime scene revealed no immediate forensic evidence of what may have occurred at the home. Investigators began piecing together Tara’s last confirmed sightings and contacts.

Sharon had last seen Tara on Monday morning, before she left for work. Tara’s coworker had last spoken with her around noon, when she said she’d stop by the mall. That was the last time anyone had heard from Tara.

When Tara’s family informed investigators that a septic company had visited on Monday afternoon, they immediately pulled information on ABC Septic and its owner, Phillip Barr. He and David McMannis both gave statements to police.

Barr stated that Tara was fine when he and McMannis left the home on Monday afternoon after the appointment. He said the two men inspected the home, entered the residence one time, and had little contact with Tara. Barr also mentioned that while in the home, the repairmen noticed a young, dark haired man in Tara’s bedroom.

Barr claimed that after he and McMannis left the McPhillips house, he stopped by Bread of Life Mission in Punta Gorda, run by a woman named Judy Jones. As far as Barr was concerned, it was a typical workday.

In the days to follow, however, investigators noticed Barr and McMannis both behaving curiously. McMannis moved out of state within a week of the incident, and the day after Tara’s disappearance, Barr was spotted, by an undercover officer, cleaning out the bed of his septic truck.

When Tara’s 20th birthday arrived on October 30, just weeks after she disappeared, there was still no sign of the young woman. Her family left birthday presents on her bed, fully expecting Tara to come home any day—to walk through the front door like nothing had changed.

By November, authorities had searched more than 500 acres of land in the Punta Gorda area, relying on helicopters, cadaver dogs, and officers on horseback to comb through remote, heavily treed areas. Knowing the family was originally from Pennsylvania, investigators followed up on leads from their previous life in the Northeast.

In November, investigators collected DNA evidence from Barr and McMannis, including hair, saliva, and blood samples. They interviewed neighbors, asking about the septic truck that had been parked at Tara’s home on October 1. One neighbor mentioned that she saw the truck, but claimed a fence between their properties made it difficult to tell who was there or what took place.

Sharon and Keith plastered the Punta Gorda area with missing person posters, from the mall where Tara worked down to Fort Myers and beyond. The flyers featured Tara’s senior picture, complete with “a smile that will knock your socks off,” in her grandmother’s words.

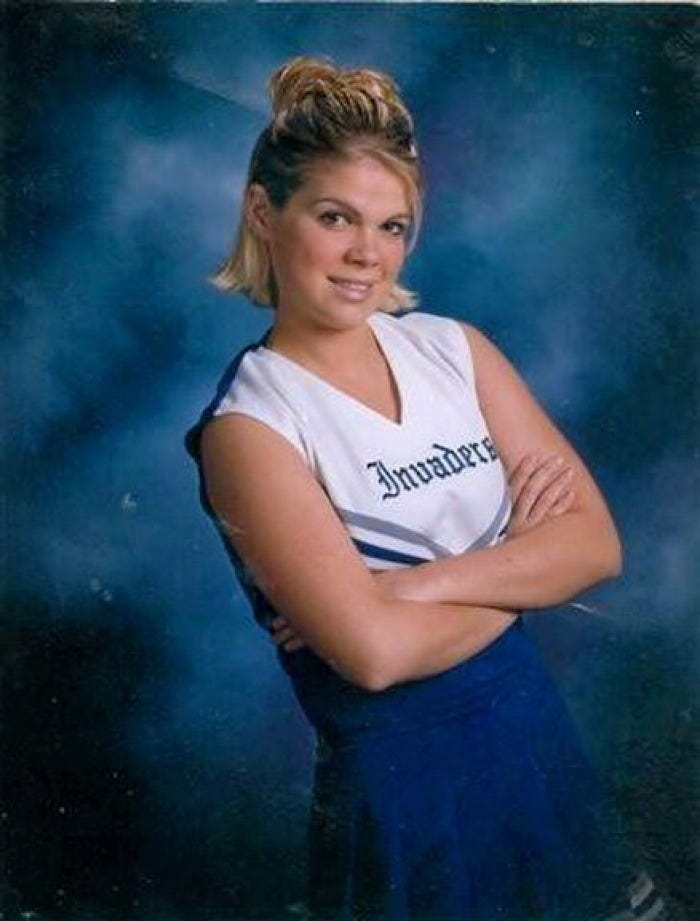

The posters described Tara as 5’5”, recently blonde instead of brunette. The young woman who had grown up cheerleading and playing softball, and who aspired to be a crime scene investigator, was now at the center of a missing persons case.

“Now someone is investigating her,” Sharon told The Scranton Times.

In March 2002, five months after Tara’s disappearance, authorities obtained a warrant to examine Barr’s truck tires, believing they matched the tracks in the McPhillips’ front yard.

Then, in April, a man named Glen St. John made an interesting admission in an interview with Florida’s Charlotte Sun. He said that a day or two after Tara disappeared in 2001, he was given stolen jewelry from Barr, who St. John had worked with on occasion. St. John claimed that he was not at Tara’s home the day she disappeared.

“Phil begged me, ‘please, please please, don’t turn the jewelry in because it came from the girl’s house,’” St. John told the newspaper. When authorities followed up on the accusation, Barr claimed the jewelry he gave St. John was unrelated and “maybe worth 10 bucks.”

St. John was on probation at the time and had turned the jewelry in to his probation officer, Scott White. In court, years later, White testified that St. John brought McMannis to the probation appointment, and that St. John’s story, White claimed, was “not consistent” over time.

The connections between Tara, Barr, and McMannis—and now, St. John—were growing, but investigators still had no physical evidence to suggest the septic repairmen were responsible for her disappearance.

Barr, in fact, began to publicly complain that the investigation was hurting his business. In a 2002 NBC segment, Barr said that he had been harassed since October 2001, and looked forward to investigators solving the case.

In June 2002, Circuit Judge William Blackwell approved a search warrant granting officers access to Barr’s home. In it, they found what appeared to be “a several-page, hand-written note” about Barr’s activities, particularly as they related to the McPhillips appointment, on October 1, 2001.

The content wasn’t publicly revealed, but prosecutors would later argue that the note was fabricated—an alibi created after Barr realized he was the prime suspect in Tara’s disappearance.

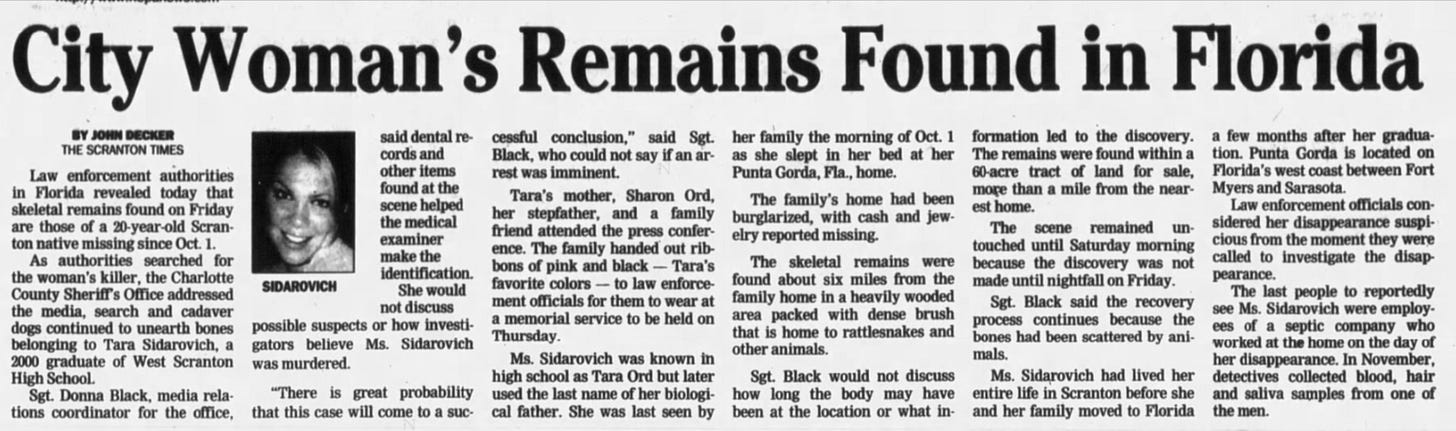

On July 12, 2002, a construction worker near Burnt Store Road, just south of Punta Gorda, wandered into the coastal brush to relieve himself. Under the humid Florida sun, the worker stumbled across what appeared to be a human skull and bones.

The remains had been scattered, likely by animals and the harsh, unforgiving climate of southwestern Florida. From where the worker stood, on a 60-acre swath of land for sale, he was more than one mile from the nearest home. He stood ten miles from Tara’s house.

When detectives arrived on the scene, they confirmed the remains were human. Sharon and Keith rushed to the area. Over the past nine months, they’d visited nearly ten potential crime scenes. But something told them this would be the last.

Eventually, dental records and a belly button worn by Tara Sidarovich confirmed that it was the missing 19-year-old. Authorities canvassed the area, but recovered fewer than half her bones. They couldn’t determine her cause of death, but did identify markings consistent with trauma to her ribs, suggesting that she had struggled mightily during the attack that ended her life.

For Tara’s family, the discovery brought devastating and mixed emotions. They had an answer to Tara’s disappearance after almost one year of uncertainty, but their loss was now permanent.

In July 2002, more than 100 friends and family gathered at Abundant Life Assembly of God in Punta Gorda to pay their respects to the bright, shining life of Tara Sidarovich. Ribbons of pink and black—Tara’s favorite colors—adorned those in attendance.

A photo slideshow captured glimpses of a painfully brief life: a young woman who loved dancing, softball, cheerleading, and Tigger, and whose charismatic presence could still be felt. A softball and glove sat beside her blue-and-gold urn. Mourners recalled the time Tara accidentally dyed her hair pink, and how she could laugh at just about anything.

“I remember one time I was walking with Tara in the hall at school,” recalled one former classmate, “and she was wearing these big platform shoes. People could see her from the classrooms, and she just fell right on her face. Then she got up and did the same thing about three minutes later. All she did was laugh, laugh, laugh.”

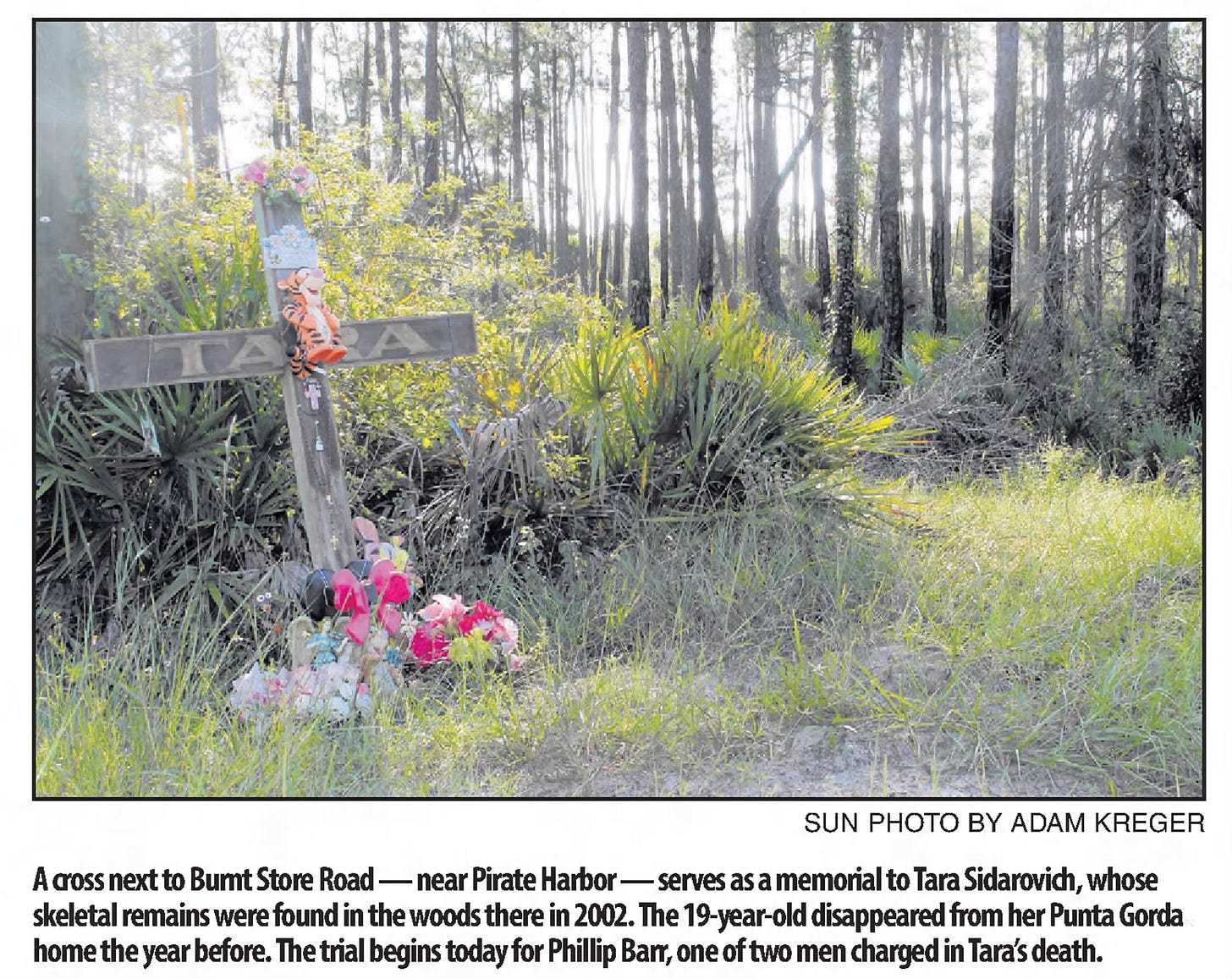

Tara’s family installed a cross near the area where her remains were found. Over the years, it would be decorated with sympathy cards, stuffed animals, fresh flowers. Detectives who worked Tara’s case left a handwritten note: We won’t forget.

And they didn’t. The month after Tara’s remains were found, detectives from Florida, Maryland, and Pennsylvania tracked down McMannis, who’d moved out of state within days of Tara’s disappearance. They reinterviewed him and several of his family members, hoping for a breakthrough.

Despite their suspicions, investigators still couldn’t piece together an ironclad case against Barr and McMannis. Tara’s home, and her remains, contained no traces of forensic evidence from either suspect. There were no eyewitnesses and no confessions, just a string of connections that were easy to follow but difficult to prove.

The repairmen’s actions following Tara’s disappearance had investigators’ full attention, but prosecutors needed stronger evidence to secure convictions.

By July 2004, Tara’s case had once again hit a wall. Barr and McMannis were still on authorities’ radar, but there had been little progress in the case for two years.

Desperate to keep momentum, Tara’s family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Barr and their landlord, Dennis Postell Jr. The civil suit, which wouldn’t impact criminal charges, claimed that Barr “abducted, kidnapped and murdered Tara Sidarovich.”

Attorney Amanda Wiggins filed the suit with Florida’s 20th Judicial Circuit, hoping the move might spur progress on Tara’s criminal case. Postell requested that he be removed from the suit, claiming that he had never permitted Barr to enter Tara’s home in October 2001. A judge denied the motion.

In July 2005, during an 11-minute deposition related to the suit, Barr invoked the Fifth Amendment ten times. He provided little information that authorities didn’t already have.

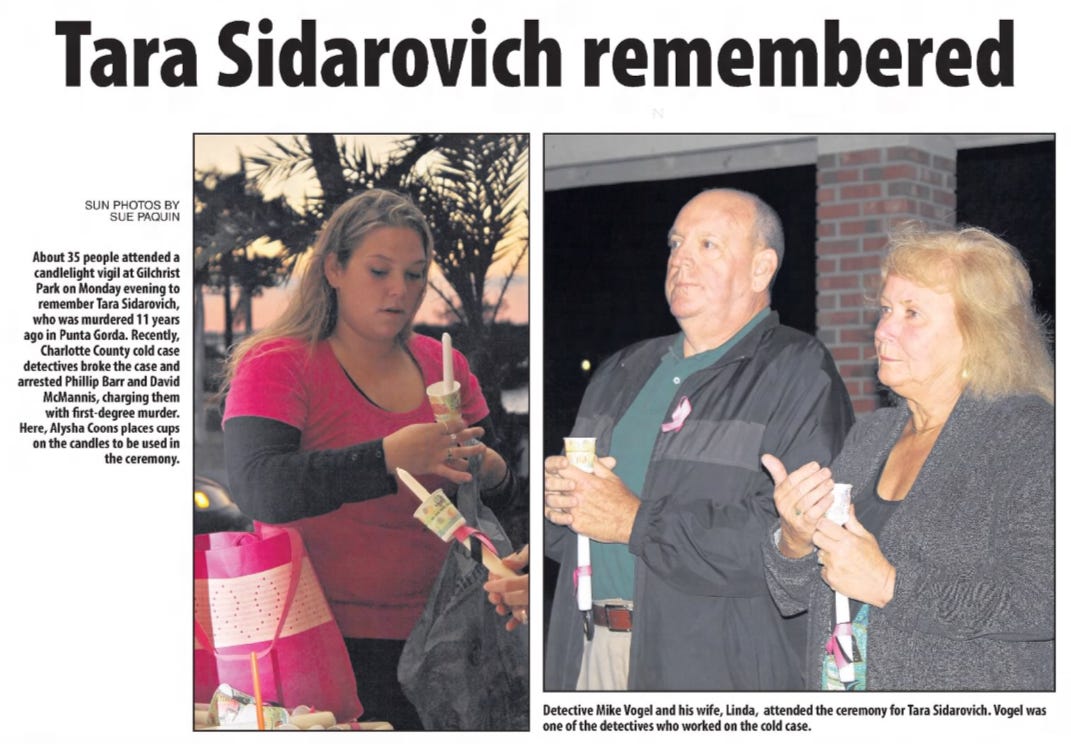

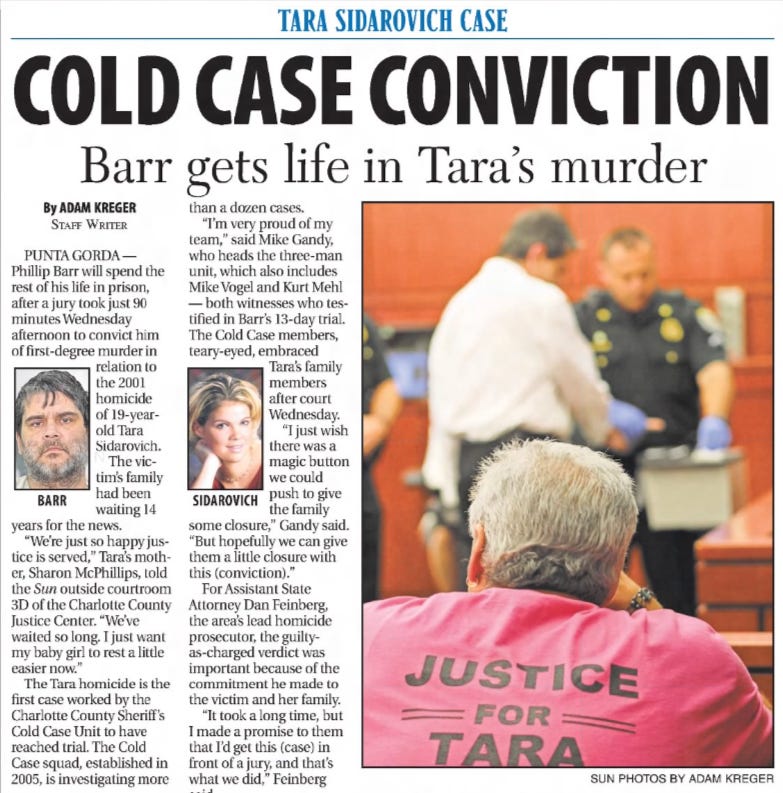

That same year, Charlotte County Sheriff John Davenport created the department’s first cold case unit. Three retired detectives—Mike Gandy, Kurt Mehl, and Mike Vogel—volunteered to work the county’s unsolved cases, including Tara’s. Gandy had been involved in Tara’s original investigation. Combined, they had more than 80 years of law enforcement experience.

The detectives hung a large print of Tara’s senior photo in the unit’s office as a reminder of what they were working toward. “When you sink your teeth into something like this,” said Detective Gandy, “you’re fighting for a helpless victim and you’re fighting for their family and friends.”

For seven more years, the cold case unit built their case piece by piece, witness by witness. They worked through at least 12 boxes of old case files and documents. In those, they began to uncover discrepancies in the initial interviews with Barr, McMannis, and Dille.

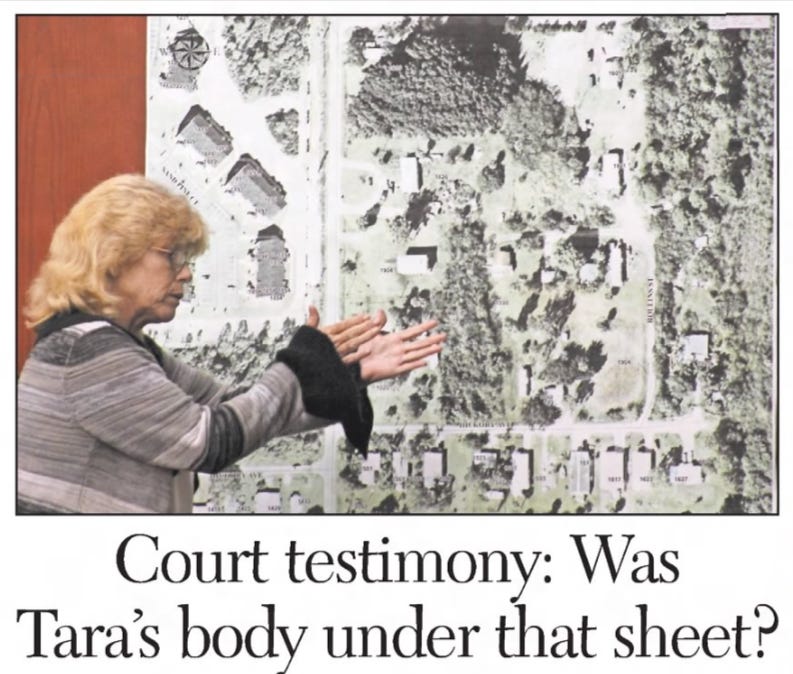

They also flagged a potential eye-witness who had not been interviewed at the time—someone who would later testify that she saw Barr and McMannis come and go to the house at least twice, including a final trip, when they backed up to the front door and unloaded the tailgate.

In 2012, the cold case detectives had finally amassed enough evidence to move forward with arrests.

On October 26, 2012, McMannis was arrested in Cumberland, Maryland, and charged with first-degree murder. An arrest warrant was also issued for Barr, but investigators couldn’t locate him. He had last been seen in upstate New York, and agencies around the Northeast began a manhunt for the murder suspect.

McMannis was soon extradited to Florida. There, he was held in the county jail without bond. The announcement of his arrest came on October 30—what would’ve been Tara’s 31st birthday.

Since Tara had disappeared in 2001, her family had begun measuring their lives in Octobers. That was the month Tara was born, when her favorite holiday arrived, and when she disappeared. Now, it was the month that investigators were finally able to make an arrest in her case.

In November, authorities announced a second arrest. Linda Fay Dille, Barr’s girlfriend at the time of Tara’s disappearance, was arrested and charged with two counts of felony perjury.

The charges stemmed from a 2001 interview, when Dille had told authorities she and Barr talked on their cell phones during the day of Tara’s disappearance. Detectives later discovered that the couple’s cell phone service had been disconnected for lack of payment at the time, making it impossible for them to have talked over those lines.

Authorities also accused Dille of lying about the location of a vehicle she owned that Barr used on October 1, 2001. During a recorded 2002 call from Barr in jail to Dille, she acknowledged withholding information about the case in 2001. “They just know I know more than what I’m saying,” she said.

On November 14, less than three weeks after McMannis was arrested, Barr was located and detained near Hardwick, Vermont. He’d been living under the pseudonym “Frank Perelli,” first at a hotel, then with a woman named Jene Mansur.

When Barr attempted to flee from the woman’s mobile home, U.S. Marshals apprehended him on the spot. According to the FBI, Barr had been supporting himself through various “fraudulent schemes” in Florida and eventually planned to head north into Canada.

Instead, Barr was finally arrested for the crime he had long been suspected of committing.

“This has been a long time coming,” said Charlotte County Sheriff Bill Cameron. “We promised Sharon we would never take our eyes off of this case.”

By December 2012, prosecutors had three suspects in custody and dozens of witnesses ready to testify. Barr and McMannis both pleaded not guilty to murder charges and were scheduled to face separate trials.

That month, Dille accepted a plea deal that would allow her to avoid prison time if she agreed to testify truthfully against Barr. If she didn’t, prosecutors said, she could face up to five years in prison.

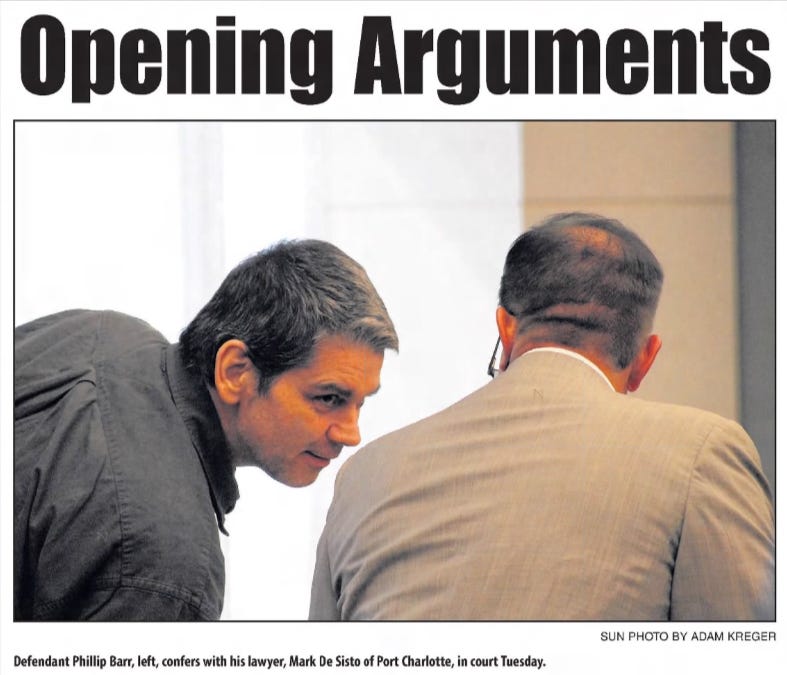

After a number of delays and legal motions, Barr finally went to trial in October 2015—14 years after Tara’s disappearance. It was the first murder trial in Charlotte County in two years, and the first trial brought by the county’s cold case unit created ten years earlier.

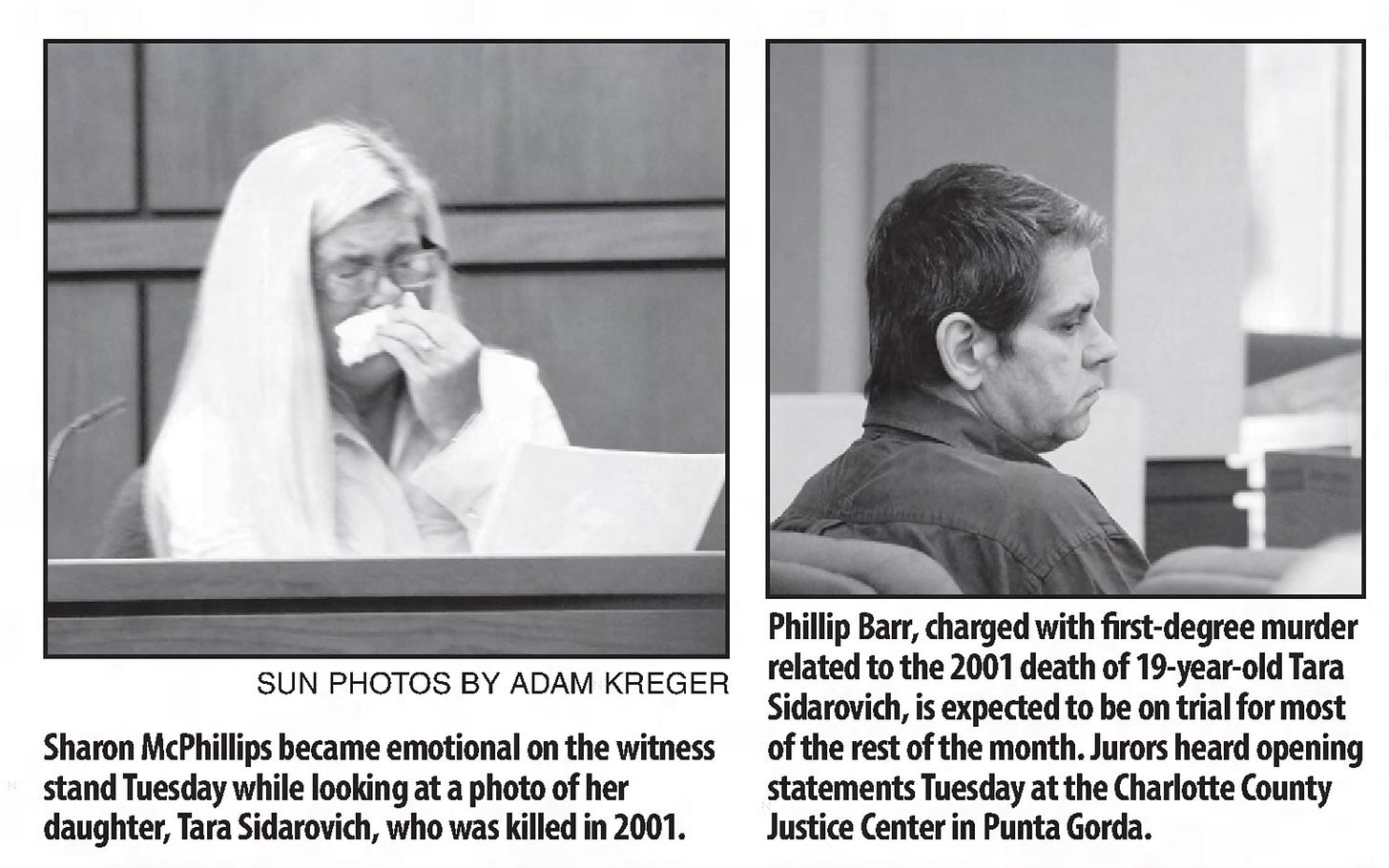

About 20 of Tara’s friends and family filled the courtroom on the trial’s first day, each wearing the black-and-pink ribbons that had become a symbol of Tara’s memory since 2001.

The state laid out its theory. On the morning of October 1, prosecutors claimed, Barr and McMannis had smoked drugs before arriving at Tara’s home. While Barr inspected the septic system, McMannis roamed from room to room, stealing jewelry and cash to fuel their ongoing drug habits. When Tara discovered McMannis robbing her home, the theory went, she confronted him and Barr.

The two men overpowered Tara, killed her, backed the truck up to the house, loaded her body, and later dumped her in the woods off Burnt Store Road. To support their case, the state planned to call 60 witnesses over a two-week period.

Defense attorney Mark De Sisto argued that Barr was guilty of one thing only: being associated with drug-addicted criminals like McMannis and Glen St. John, who had received immunity in the case thanks to information he disclosed to investigators.

De Sisto emphasized that no DNA evidence had ever linked Barr to the crime, and suggested instead that the emotional pull of the cold case led investigators to develop “tunnel vision” on his client.

De Sisto pointed out that McMannis had left the state shortly after Tara disappeared, and said that her remains were found not far from one of St. John’s favorite fishing holes. Barr’s judgment of character was poor, he admitted, but he was not responsible for Tara’s murder.

Weeks of testimony and circumstantial evidence outlined what investigators knew of the case. Dr. R.H. Imami confirmed that Tara’s rib bones had shown signs of trauma, but noted that because so little of her skeletal remains were recovered, her exact cause of death still couldn’t be determined.

Damning evidence came from witnesses who testified that Barr made incriminating statements in the days, months, and years following Tara’s disappearance. “By the time they find her body, it’ll be totally decomposed,” Barr allegedly told one Charlotte County Jail inmate, according to the inmate’s testimony.

Another inmate, who testified that Barr appeared worried about Tara’s case in 2002, said Barr told him the young woman “won’t be talking.” A woman who saw Barr at Harpoon Harry’s on the night of October 1, 2001, said he appeared “dirty, like he had been working all day,” with visible marks on his upper left arm.

But the most damaging testimony came from Barr’s ex-girlfriend.

Dille, who had chastised the media for harassing Barr during the investigation’s early days, testified that his behavior on the day of Tara’s disappearance was out of the ordinary.

She claimed that on October 1, 2001, Barr asked Dille to borrow her Toyota Corolla so he could remove a “hog carcass” near their home.

When Dille saw something under a sheet in the car, she didn’t question it at the time. Later, Dille said, she realized it might not have been a hog at all. After Barr borrowed the Corolla that day, she never saw the vehicle again—something she’d failed to mention to investigators during her earliest interviews.

“I just forgot about it,” Dille said during the trial. “I wasn’t trying to mislead anyone.”

Barr also asked her strange questions on October 1: How do you clean up DNA evidence? Where’s a good place to dispose of a body?

He also loaded bedsheets into the washer that day—something Dille said he would never do on his own. To prosecutors, and the jury, these erratic and out-of-character behaviors presented a clear pattern.

On October 28, 2015, a jury of seven men and five women deliberated for less than 90 minutes before finding Barr guilty of first-degree murder. He was immediately sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Charlotte County’s first cold case conviction was complete.

In February 2017, following a six-week trial, McMannis was also found guilty of first-degree murder. His jury took less than one hour to reach their verdict, and McMannis, too, was immediately sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Sixteen years after Barr and McMannis backed their septic truck up to the McPhillips’ front door, both men had finally answered for what they’d done.

Detectives Mike Gandy, Kurt Mehl, and Mike Vogel did what their note on Tara’s memorial promised. It took years of persistence, but they kept their word.