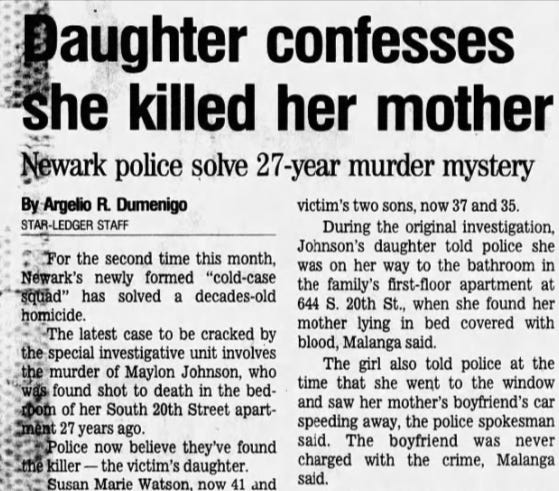

The Cold Case of Maylon Johnson

When a city's new cold case unit broke ground in 1998, two brothers asked detectives to find the person responsible for their mother's 1971 murder. The answer was closer than the brothers realized.

On September 1, 1998, Newark Police Director Joseph Santiago formalized the city’s first Cold Case Squad, a unit dedicated to working older unsolved cases, some of which dated back decades.

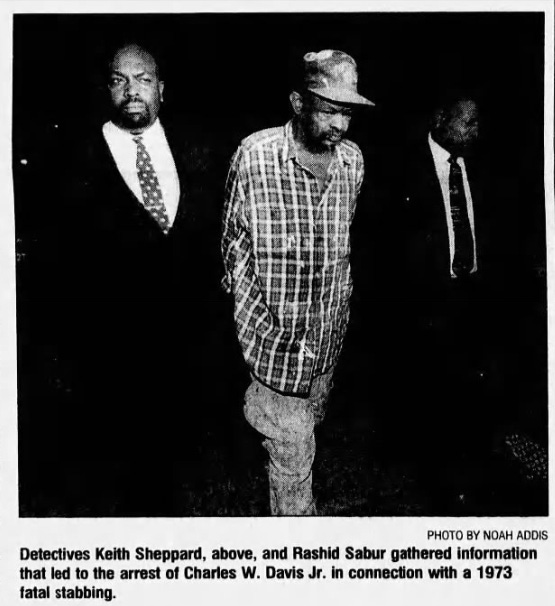

Detectives Keith Sheppard and Rashid Sabur were assigned to review dust-covered, well-worn case files and field phone calls from families who had never stopped searching for answers.

Within a month, they’d already solved and closed their first case: the 25-year-old murder of Theodore Mitchell, a dry cleaning business owner who’d been stabbed to death in his storefront in March 1973.

The detectives tracked down a witness who had been only nine at the time of the crime, but was now 34 and able to identify the murderer as Charles Davis Jr.

The unit’s early success made headlines in Newark. In October, two brothers contacted the squad with a 27-year-old cold case of their own.

In the early morning hours of October 3, 1971, 10-year-old George Johnson woke to the sound of screaming.

His older sister, 14-year-old Susan Marie Johnson, was shrieking in distress from their mother’s bedroom. George and his brother, 8-year-old David Johnson, ran down the hallway to her room in their first-floor apartment on South 20th Street in Newark, New Jersey.

Their mother, 30-year-old Maylon Johnson, lay in her bed with a single bullet hole in her chest and nightclothes. Susan was in the room, crying and yelling.

When police arrived, Susan told them she’d woken to a loud noise. When she went to check on her mother, she found Maylon shot and already deceased. Susan went to the window, she reported, and saw her mother’s boyfriend’s car speeding away from the scene. Maylon was separated from Susan’s father at the time, and had a steady boyfriend—someone Susan did not like or trust.

Authorities questioned Maylon’s boyfriend, but he was quickly cleared and never considered a suspect in the murder. Investigators interviewed neighbors and those who knew the single mother, but were unable to uncover any leads in her case, which soon went cold.

It remained that way for 27 years. But when George and David overheard that Newark’s newly formed cold case unit was fielding calls, they got in touch with detectives Sheppard and Sabur.

The brothers had a working theory: their mother was seeing a second boyfriend in October 1971, they believed, and this unknown man may have shot and killed her out of jealousy.

As they did with the Mitchell case, Sheppard and Sabur began reviewing the investigation’s original findings. They pored over every document, interview statement, and every scrap of evidence that had been preserved from 1971.

It was then that Detective Sabur found something that the first investigation had overlooked. It was a minor detail, easily missed, but one that pointed in the direction of who might’ve been responsible for Maylon Johnson’s murder.

In October 1998, Sheppard and Sabur began reinterviewing witnesses and persons of interest from 1971, including the Johnsons’ former neighbors on 20th South Street, as well as previous addresses. They also tracked down Maylon’s daughter, Susan Marie Watson, in Schenectady, New York—about three hours north of Newark.

Susan was now 41, married to a counselor named Michael Amos, and working as a keyboard operator for The State University of New York. She and Michael had three daughters, and Susan spent her free time volunteering at a group home for troubled girls. She was generally known as a reserved person who went out of her way to help others when she could.

In late October, Susan agreed to come to Newark to talk to detectives about her mother’s murder. On October 28, she arrived at the Newark police department and was led into an interview room.

For hours, detectives Sheppard and Sabur asked Susan about what she could recall from that morning 27 years ago. But they had another motive: they wanted to build rapport with Susan. They asked her about her childhood, her relationship with her mother. The boyfriend.

Susan revealed that she had often been abused by her mother—verbally and physically. Maylon frequently berated and beat her three children, Susan said, and her boyfriend had also sexually abused Susan.

Life in their apartment, in Susan’s view, had been violent and traumatic. Susan felt like her mother not only abused her and her brothers, but did nothing to prevent others from doing the same.

The detectives listened intently, watching Susan’s body language and tone change over the course of several hours. Finally, Susan broke down.

In tears, she confessed to murdering her mother in October 1971. Now an experienced mother herself, Susan finally admitted to what had happened nearly three decades prior.

When her husband later asked why she’d confessed then and there, to complete strangers, Susan had a simple answer.

“I trusted them,” she said.

Susan’s confession hardly surprised Detective Sabur.

“I said, ‘She’s gonna lie, she’s gonna lie,’” he said after the interview. “But then she’s gonna tell the truth.”

Sabur had discovered early in their cold case investigation that Susan’s original police interviews included, in his words, “a lot of dancing around.”

The small detail that seemed to be overlooked the first time around? The medical examiner determined that when police arrived on the scene, Maylon had been deceased for about two hours. For three young children who’d suddenly and shockingly lost their mother, Sabur thought, that two-hour gap didn’t make sense.

“My thing is, being the suspicious person that I am,” said Detective Sabur, “that this girl waited two hours to get her story together because she killed her mom.”

Sabur’s theory was that Susan fired the shot, then staged her shock and distress when George and David rushed in. The boyfriend’s car fleeing the scene was fiction—a misdirection she invented during those two hours of waiting.

The truth was that Susan believed the household’s abuse would never stop unless she stopped it herself.

Susan admitted that in the early hours of October 3, 1971, she crept into her mother’s room and opened a nightstand drawer, where Maylon’s handgun lay wrapped in a handkerchief.

Susan unwrapped it, aimed it at her mother, still sleeping in bed, and fired a single bullet into her chest. She quickly wiped her fingerprints with the handkerchief and placed it back in the drawer.

Then she hid behind the window curtains. Maylon, in shock, sat up in bed—now bloodied and panicked—and called her daughter’s name. Just as suddenly, she fell back and died.

Susan waited, and worked through what would become her alibi. She waited for her brothers to come in and considered what she’d tell them. What she’d say to the police. Although she was questioned and interviewed at the time, investigators never seriously considered Susan a viable suspect.

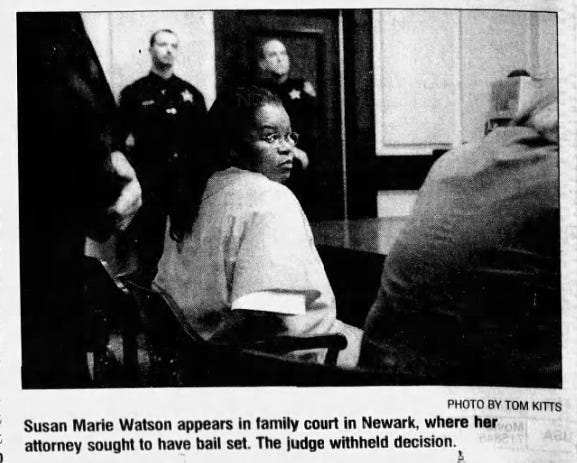

Upon her confession, Susan was arrested and charged with murder. But the case immediately presented a legal paradox for authorities. Because she was only 14 at the time of the crime, Susan was booked as a juvenile offender and held at Essex County Juvenile Detention Center.

Ray Weiss, spokesperson for the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office, said that the unusual case could result in Susan being tried as an adult, but that the county would make that determination in the near future.

In the meantime, the 41-year-old was placed in a separate wing of the juvenile facility, beginning a process that would become years of legal uncertainty in uncharted territory for the county’s court system.

Before South 20th Street, the Johnsons had lived on South 15th Street, in an apartment below Barbara Evans and her sister, Carol. When the sisters were interviewed in 1998, neither was surprised by Susan’s confession.

“She used to beat them for hours at a time,” Barbara said. “She would turn on the radio real loud, but I would hear them crying all three of them.”

Carol confirmed that the Evans family could hear, on a near-daily basis, the verbal and physical abuse that took place in the Johnson household. “When I first read about Susan, a friend of mine was sitting here with me, and I said, ‘I’ll be damned. I knew this kid. I can imagine how she felt all these years.’”

Curiously, the Johnsons’ previous neighbors on South 15th Street were never interviewed by police in 1971. If they had been, investigators might have looked closer at what went on inside the home rather than who may have been fleeing from it.

Susan’s neighbors may have understood her predicament, but Detective Sabur had little sympathy. Even if Maylon had abused her children, Sabur said, she didn’t deserve to die like that. Susan, however much a victim herself, would still have to face her legal consequences.

Those consequences, however, were difficult to determine. Within days of Susan’s arrest, Family Court Judge Michael Degnan instructed that she be moved to an adult facility, but it still wasn’t clear if she would face murder charges as a juvenile or an adult.

According to the laws that were in place when the murder was committed in 1971, a 14-year-old in New Jersey could not be tried as an adult. The maximum penalty a juvenile could receive back then—even for murder—was being detained until they were 21. The focus of juvenile penalties at the time was rehabilitation rather than extended incarceration.

By 1998, the penalties for juveniles had changed. Now, a 14-year-old convicted of murder could be held for up to 20 years. This presented the court with a unique challenge: based on 1971 laws, Susan couldn’t be charged as an adult, but by the time she was arrested in 1998, she was well past the age of a typical juvenile defendant in need of rehabilitation.

“In my 18 years in Superior Court,” said Family Court Judge Michael O’Brien, “I haven’t seen it. It’s very, very unusual.”

In early November, Susan’s defense attorney, Walter Florczak, argued for her to be released on bail, claiming that since the shooting in 1971, Susan had led a normal, law-abiding life that was stable and uneventful. While the judge deliberated, Susan remained at Essex County Jail Annex in North Caldwell, housed among adult inmates.

The prosecutor’s office requested that Susan be held on $150,000 bail, but Judge Degnan soon decided her bail would be set at $10,000. She was released in early November, as the Superior Court’s adult and juvenile divisions worked to decide where she would be prosecuted.

During initial hearings, Florczak attempted to have the media barred from the proceedings, but Judge Degnan denied the motion and allowed media, including reporters from The Star-Ledger, into the courtroom.

By early 1999, after months of legal wrangling, it still wasn’t clear whether Susan would be tried as a juvenile or an adult.

Frustrated with the lack of progress and aware that his client faced a sort of legal purgatory, Florczak filed a motion to dismiss the charges against Susan in February 1999, claiming that no court had proper oversight over her case.

“No one has jurisdiction because the law simply doesn’t provide for dealing with 41-year-old juveniles,” Florczak said.

He argued that Susan had already done what juvenile detention was supposed to accomplish: she’d rehabilitated herself. She had raised a family, held steady work, and became a productive member of society. Time, Florczak argued, had been her sentence, and she’d served it in the community instead of behind bars.

In April 1999, six months after Susan confessed to murdering her mother, Judge Degnan ruled that she could go free.

Because 1971 statutes didn’t allow 14-year-olds to be tried as adults, the judge declared, she couldn’t be moved to an adult court. And because juvenile law at the time focused on rehabilitation—something Susan had clearly achieved—there was no point in further pursuing the case.

“There is absolutely no purpose in prosecuting Miss Watson,” the judge said in his ruling, “and clearly no need to rehabilitate.”

When the judge announced his decision, Susan broke down into tears, embraced her husband, and hugged her brothers, who sat behind her. David celebrated his sister’s legal freedom, but George did not.

“She should have been punished,” he said afterward. “She killed my mother. I suffered for 27 years.”

Despite numerous testimonies stating that the Johnson children were routinely abused, George, who was only ten at the time of Maylon’s murder, remembered something different. He recalled a single mother who worked hard to keep a roof over their heads and food on the table.

“My mama worked two jobs to get us everything we wanted,” he said in 1999. “She wanted better for us.”

To George, Judge Degnan’s ruling meant that Susan had gotten away with murder.

The prosecution agreed: though Susan did appear to be rehabilitated, and though she murdered Maylon under abusive conditions, it was a crime nonetheless—one Assistant Prosecutor Keith Harvest believed should have consequences in some form, even if those were unclear.

“The mere fact that she was undetected should not benefit her,” Harvest said to the judge after the decision was announced.

A hearing following the judge’s ruling would determine whether Susan was indeed rehabilitated, but attorneys from the prosecution and defense agreed that this was a mere formality.

The judge had made it clear: this case appeared to be over.

In February 2000, nearly a year after Judge Degnan dismissed Susan’s charges, a Superior Court panel reversed the decision. It ruled that Susan would be required to face her original charges in juvenile court.

A two-judge panel determined that, despite her age and the time that had elapsed, the juvenile court was the proper jurisdiction because of Susan’s age at the time of the murder.

The panel also determined that Judge Degnan should have established guilt or innocence before separately addressing Susan’s rehabilitation. It was a technicality, to be sure, but one that meant Susan would have to return to court and face murder charges after all.

With her charges reinstated, Susan was scheduled to face trial in June 2001. But just days before the trial was to begin, Susan and her defense attorney negotiated a plea deal: she would plead guilty to manslaughter—a reduced charge with an expired statute of limitations—in juvenile court.

Susan offered a tearful apology, repeating that her actions in October 1971 were a result of her mother’s repeated abuses and her inability to stop others from doing the same. After Susan entered her plea, Judge Degnan held a hearing, another formality, to officially declare Susan rehabilitated.

To some degree, the plea deal allowed all parties to save face. Susan admitted to the crime. Assistant Prosecutor Harvest appreciated the admission, and defense attorney Florczak believed it to be a fair conclusion.

Through her lawyer, Susan—who didn’t give media interviews during the case—made it clear that she wanted to keep the past in the past.

“She wanted to plead because she didn’t want to put her mother on trial,” Florczak said after the judge’s final ruling.

George Johnson finally had the answer he and David sought when they contacted the newly formed Newark Cold Case Squad in October 1998.

But there was no jealous second boyfriend, no person who slipped away in the quiet, early hours of October 3, 1971. There was only a daughter, an older sister, who screamed for help, yet again, in her South 20th Street apartment.

Thanks for reading Buried Cases. If you found this story interesting, send it to a friend to help this project grow. You can also explore past reads, like:

Have a case you’d like to see covered? Let us know here.

What a shock that must have been to these brothers. All families deserve to know who killed a loved one, but justice was so complicated in this case. I hope they have found some peace.